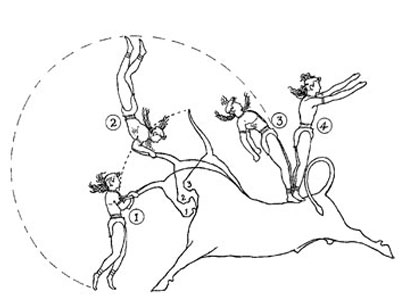

a mythological poetic story about a nervous yet brave novice bull-leaper (inspired by “The Bull-Leaping Fresco” and Martis, the main character of Eleanor Kuhn’s book “On the Horns of Death”)

Body frozen in place by neophyte’s first-leap nerves.

Neither a blink nor a breath as she nears her turn.

First, it is her soul who leaps out of her chest and enters the ring

as a bull white as ivory charges towards her in full swing,

galloping hooves syncing with her quickening heartbeat.

And so, she grabs the creature by the horns and flips,

ironclad her determination and grip,

then smooth as still sea, vaults over its back,

landing feet first assuredly upon the sand.

But as her turn arrives in real-time, she averts her eyes

and side-steps, barely veering from her demise.

Her fellow leapers try to pull her from the bull’s line of sight,

yet she remains a pillar unmoving; she must give it another try.

So, as the bull comes back around,

heaving as it tires from countless rounds,

she takes a deep breath and braces herself,

and as if divinely guided by The Goddess,

grasps the beast by the horns with calloused hands,

vaults, and lands, freezing in place upon his coarse back.

Her arms quiver in both excitement and fear

while her comrades gasp and cheer.