The Cretan goat (or kri-kri) is a creature of Minoan times that is still in existence to this day. It’s considered a feral goat endemic to Crete that also happens to be the island’s main symbol. This particular goat is commonly referred to as an agrmi (αγρίμι: “the wild one”, wild beast” or “full of fury”) amongst Cretans. Its female counterpart is called a sanada (σανάδα).

Key Traits of the Cretan Goat

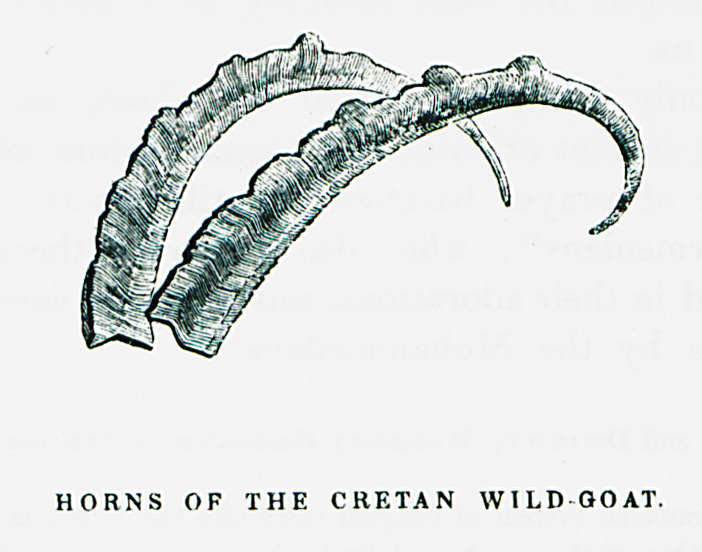

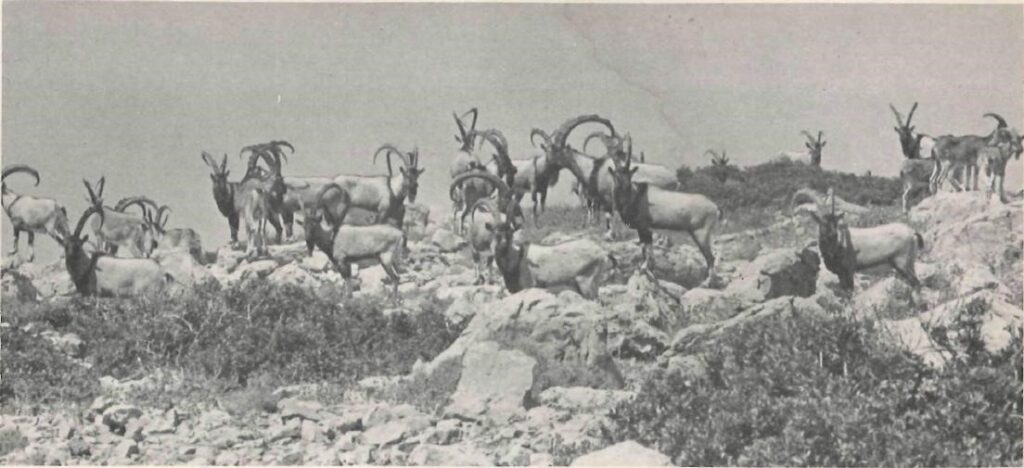

The kri-kri’s coat is coarse and light brown, with a black band around the neck on males. Moreover, it’s a double coat, consisting of an outer layer of longer, coarser hair (guard hair) and a soft undercoat (underwool). Their two horns that curve back are noticeably longer on agrimia than sanades. As for their extra-long hooves, they are cloven, which means that they’re split into two main hooves that work independently of one another. It also has two dewclaw hooves higher up its pastern (ankle), which are ideal for climbing cliffs and landing their large leaps without falling.

Out in the wild, the Cretan goat possesses a timid demeanor and avoids humans whenever possible but when cornered or taunted, they may respond by lowering their heads, pulling in their chins, and showing their horns.

The Agrimi’s Origins

The agrimi was most likely imported to the island during the Minoan period. Molecular analyses also demonstrate that this goat is not considered a distinct subspecies of wild goat as formerly posited. It is, in fact, a feral-domestic goat obtained from the initial stocks of goats domesticated in the Levant and various parts of the Eastern Mediterranean in approximately 8,000 BCE.

A Protected Species That’s Still Under Threat

Capra hircus cretica was once common throughout the Aegean but the peaks of the White Mountains of Western Crete are presently where its most prevalent. This area hosts over a dozen endemic species and is protected by UNESCO’s (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) Biosphere Reserve in Samaria Gorge. Agrimia also extend into the Samaria National Forest and the isles of Dia, Thodorou, and Agioi Pandes. To grow their numbers, they’ve recently been introduced onto two additional islands.

Despite all these efforts, the kri-kri is deemed “Near Threatened” globally by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) as of 2025 due to habitat loss, hybridization with domestic goats, and poaching.

Back in 1960, this emblematic animal was at its most threatened, with a population just over 100. The main reason for this is that it had been the only meat source available to freedom fighters during World War II’s German occupation. Thankfully, Samaria Gorge became a national park two years later!

A Sacred Symbol

Not only is the kri-kri a primary symbol to modern-day Cretans, but it was also sacred in antiquity. Many depictions have been found by archaeologists in Minoan art, including the Minoan rhyton (drinking vessel) pictured above. This has caused some academics to surmise that the Cretan goat was worshiped and had ties to the Greek god Pan, the half-goat deity who presided over the wild, shepherds, and flocks.

Today, the agrimi represents the free spirit, grit, and determination of the Cretan people. It also embodies the island’s rugged landscape and the perseverance necessary to traverse it. I didn’t understand the reference at the time, but I’d be compared to an agrimi as a kid when I’d be outside playing with my friends all day long, paying no mind to skinned knees, sweaty clothes, and dirt on my hands and legs. “The Wild One”… Quite fitting indeed.

Sources

- Bar-Gal, G. K. et al.: Genetic evidence for the origin of the agrimi goat (Capra aegagrus cretica). Journal of Zoology.

- Breed Profile: Kri-Kri Goat by Tamsin Cooper

- Manceau, V. et al.: Systematics of the genus Capra inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.

- Minoan Zoomorphic Culture by Emily S.K. Anderson