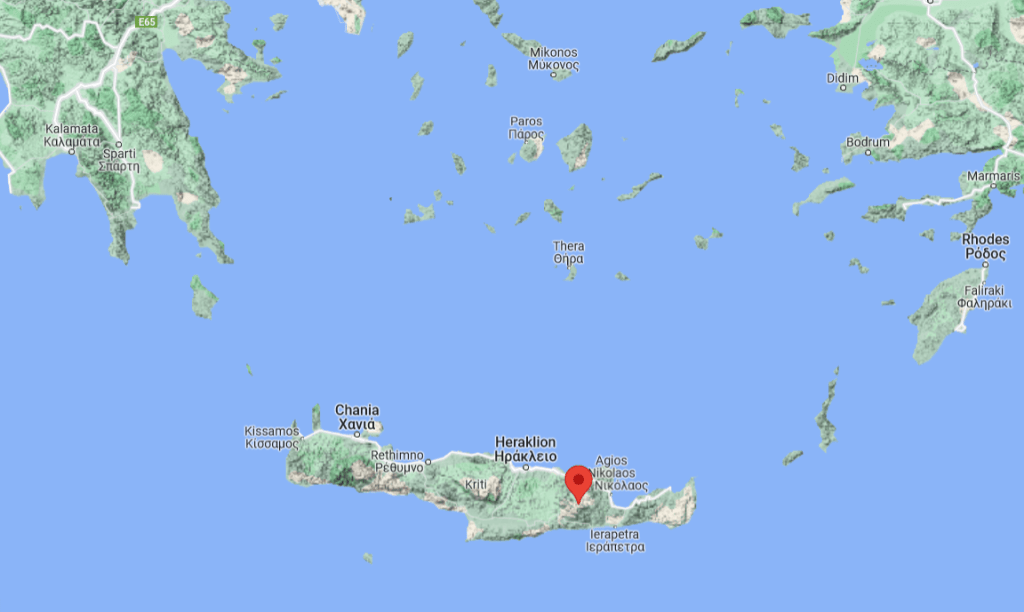

When one hears “Ancient Crete,” The Minoans come to mind, and while that is a key milestone in early Cretan history, that’s not the entire story. Below are some key happenings up until 395 CE. Seeing as this is a Minoan-focused blog, details will be mainly included for events pertaining to the Minoan civilization and what led up to it.

130,000 BCE:

First Signs of

Human Activity on Crete

The first sea-crossing in the Mediterranean was thought to have occurred around 12,000 BCE, but 130,000-year-old stone tools that were discovered during excavations in 2008 and 2009 say otherwise. This means archaic sea-faring humans had been visiting the island far before then. For thousands of years, Crete was ecologically isolated, with only several animals inhabiting it (i.e., dwarf elephant, Cretan owl (Athene cretensis), shrews, otters, and small deer).

7,000 BCE:

Beginning of

Crete’s Neolithic Era

This marks the initial habitation of the island by Anatolian settlers.

6,000 BCE:

Initial Habitation of Malia

(Neolithic period)

Near a fertile plain on the northern part of the island with its own harbor, it’s no surprise that people gravitated towards this area. Malia later became one of the Minoan civilization’s major settlements.

3,600 BCE:

Initial Habitation of Phaistos

Yet another fertile part (the Mesara plain) of the island was inhabited at around this time.

3,000 BCE:

Emergence of Stone Tombs

& Large-Scale Buildings

2,700 BCE:

Emergence of Olive Trees

Olive trees were grown and their olives and olive oil were exported. The oldest living olive tree in Crete is The Olive Tree of Vouves, said to be 3,000-4,000 years old!

2,200 BCE:

First Monumental

Architecture at Malia

Initial Malian architecture consisted of a monumentalized court, in an attempt to bring nature-based ritual to an indoor environment.

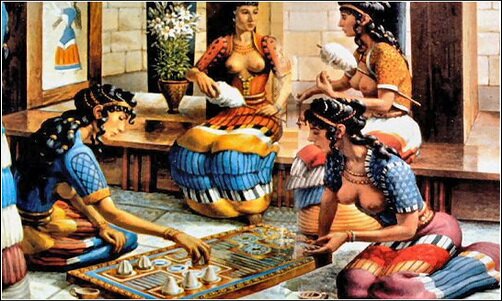

2,200-1,500 BCE:

Peak of

The Minoan Civilization

In this span of nearly a thousand years, the Minoans flourished, and their king established the first-ever navy regionwide.

2,000-1,700 BCE:

Phaistos at

Its Cultural Height

Phaistos was one of the most prominent centers of Minoan civilization. Its first Minoan palaces were built at this time.

2,000-1,450 BCE:

Zakros at

Its Cultural Height

Zakros was enveloped by mountains and situated in a gulf in south-eastern Crete. Again, the fertile land it was upon ensured its prosperity.

2,000 BCE:

First Pottery Wheel

The introduction of the pottery coincided with the Minoan’s agricultural lifestyle, where robust vessels (i.e., pithoi) were needed.

2,000-1,650 BCE:

Emergence of

Cretan Hieroglyphic Script

Cretan hieroglyphics are the oldest identified script in Europe and are undeciphered to this day.

1,900 BCE:

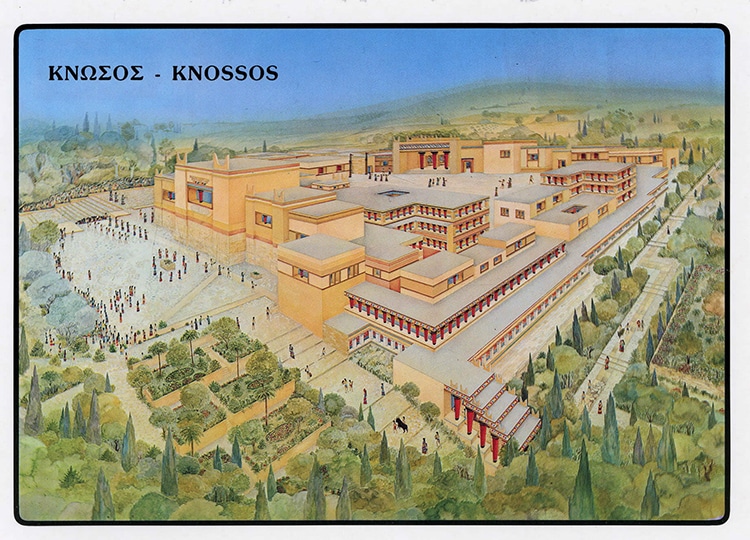

First Minoan Palace

at Knossos

On the outskirts of Heraklion, Knossos was the most prominent site of the Minoan civilization. It is best known as the palace of King Minos and his daughter, Princess Ariadne, as well as the Greek myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. It is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Crete to this day. To see photos I took of the palace, go here.

1,850-1,450 BCE:

Emergence

of Linear A Script

Linear A was syllabic Bronze Age script consisting of at least 90 characters and over 800 words. The fact that it was composed of clustered lines in abstract formations has made it almost impossible to decipher. However Linear B, which uses 70% of Linear A’s characters has been deciphered, so that gives linguists hope.

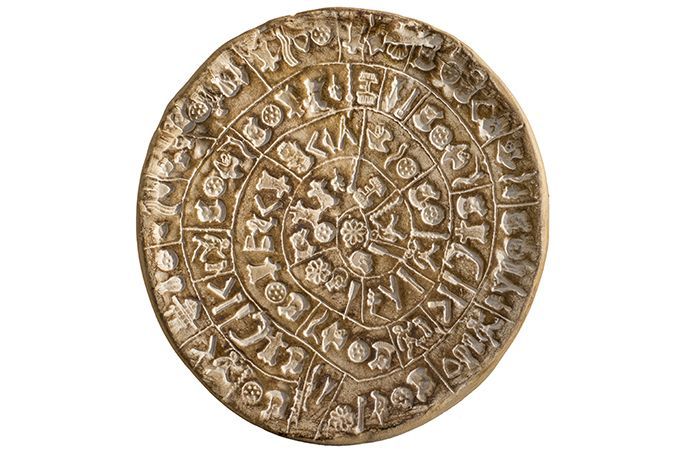

1,850-1,550 BCE:

Creation of

The Phaistos Disk

The Phaistos disk was made of fired clay and engraved with 242 symbols in a spiral formation on both sides. It also remains undeciphered.

1,700 BCE:

Second Phaistosian

& Knossian Palaces

1,675 BCE:

Second Malian Palace

1,600-1,500 BCE:

Knossos Survives

Thera’s Volcanic Eruption & Tsunami

Upon the volcanic explosion at Thera, ash covered most of Crete’s northern coast. Despite surviving the eruption, Knossos lost its momentum thereafter due to damage of trade routes, continual looting, etc.

1,600 BCE:

The Beginning of the End

for Minoan Civilization

While some settlements weren’t entirely decimated, many settlements were. This greatly weakened the Minoans as a whole.

1,450 BCE:

End of Malia’s

Minoan Period

A devastating earthquake and fire brought an untimely end to Malia’s thriving Minoan period.

1,450 BCE:

Destruction of

Zakros’ Minoan Palace

Despite being in a gulf sheltered by mountains, the palace at Zakros wasn’t exempt from damage.

1,450 BCE:

Start of Mycenaean

Influence in Knossos

The Mycenaeans (a civilization from southern mainland Greece) were a more militaristic power and considered a warrior society, mirroring that of The Spartans. As such, they overtook the remaining Minoan settlements. Already weakened by natural disasters, The Minoans were unable to adequately defend themselves.

1,300 BCE:

Abandonment of

Zakros Settlement

1,100 BCE:

The Minoan Civilization’s

Official Demise

The deteriorating economy, dwindling population, and natural disaster aftermath was just too much. At this point, The Mycenaeans took full control of Crete and adopted Minoan culture. In turn, “Mycenaean culture” heavily influenced classical Greek culture. However, their reign over Crete didn’t last long (Mycenaean civilization ended in 1,150 BCE).

700-600 BCE:

Brief Resurgence

of Phaistos

690 BCE:

Introduction of Coinage

Gortyn created its own coinage. Gortyn was a settlement on the Mesara plain of central Crete.

220 BCE:

Gortyn’s Allyship

with Knossos

In order to defeat Lyttos (another ancient Cretan settlement) during the Lyttian War, the two settlements banded together. Knossians took advantage of the Lyttian’s absence due to a distant voyage and caught them by surprise, ultimately bringing them to their demise.

206-204 BCE:

War Between

Crete & Rhodes

180 BCE:

Gortyn Conquers Phaistos

155-153 BCE:

Second War

Between Crete & Rhodes

110 BCE:

Peace Established Between

Warring Cities by Rome

71 BCE:

War Waged by Romans

Against Cretan Pirates

36 BCE:

Crete Gifted to

Cleopatra by Mark Antony

60 CE:

Emergence of Christianity

in Crete (Gortyn)

395 CE:

Crete Conquered by

The Byzantine Empire

*Photos from Wikimedia Commons unless otherwise specified, and I used info from WorldHistory.org to construct the timeline.