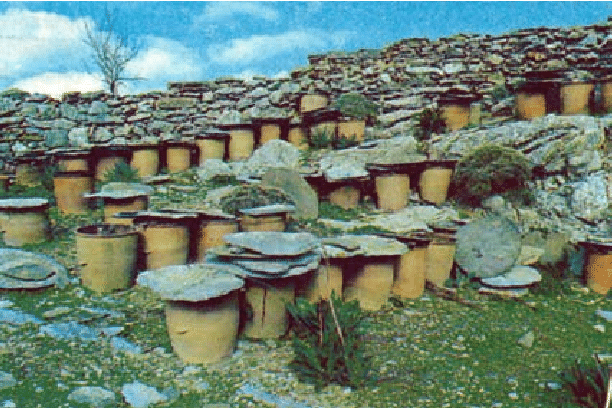

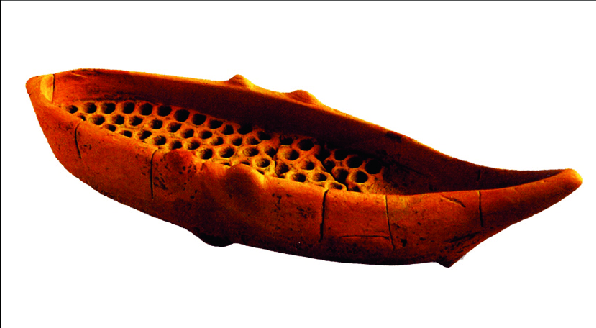

Beekeeping equipment, beehive fragments, and depictions of beehives that date all the way back to 1,700 BCE are amongst various archaeological findings on the island of Crete and Thera. From The Malia Pendant that depicts two conjoined bees to remnants of honey offerings to their deities, bees (and the honey they produced) were integral symbols to the Minoans.

Bees in Minoan Art

With how intrinsically connected the Minoans were to nature, it’s no surprise that bees and honeycombs were a recurrent motif in their frescoes, pottery, seals, and more.

The Bees of Malia

While archeologist Dr. Georgios Mavrofridis and some of his colleagues posited that The Malia Pendant was modeled after the mammoth wasp (Megascolia maculate), The Malia Pendant (Χρυσό κόσμημα των Μαλίων) and “The Bees of Malia” are used interchangeably. At first glance, the impression that these may be wasps instead makes sense, if it wasn’t for the Minoan’s tendency to distort, and in most cases exaggerate, the forms of creatures and humans alike in their art. Realism just wasn’t of primary focus. This embellished art style was also evident in Egyptian art, which directly inspired them. For instance, the elongated thorax and abdomen bees were often depicted with at that time emphasized fertility. Furthermore, The Malia Pendant showcased the production cycle of honey, and thus, the inescapable cycle of life and death.

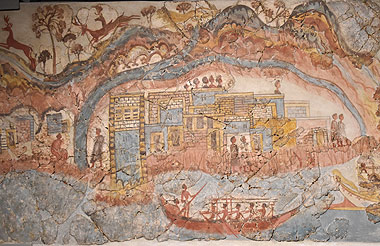

Miniature Frieze from Akrotiri

A potential apiary (a place where bees are kept) is depicted in the structure painted on the south wall of the Miniature Frieze from the West House at Akrotiri, Thera. Covering the slope of a hill, it comprises dual vertical blue bands on its western edge as well as four horizontal blue bands, five rows of black triangles with circular openings at their base alternating with the aforementioned bands. In addition to an apiary, this has been deemed a shipshed, storage area, and more.

However, there are several uncanny details that lean towards the apiary interpretation. For instance, the triangular aspects likely depict the fixed-comb beehives that are still used in Greece to this day. Moreover, the path that goes from the apiary and joins the settlement with the three-part building at the hill’s zenith may signify organized beekeeping. The trapezoid-shaped expanse of blue to the east possibly portrays a pond (a water source being another vital aspect of beekeeping). While theoretical, researcher Irini Papageorgiou believes the scope of the area encompassed by the installation and the prominence of beekeeping products (indicated by both chemical analysis and Linear B tablets references) do, in fact, point to an apiary.

Honey: Ambrosia of the Minoans

Honey was utilized in numerous areas of Minoan life, making it almost if not just as valuable as olive oil. With how ubiquitous of a commodity it was, this liquid gold had multifaceted symbolism to match.

Honey in Minoan Religion

Based on archive tablets found at Knossos, it was noted that honey offerings were made to the pre-Hellenic goddess based out of Crete, Eileithyia (goddess of childbirth and midwifery). More specifically, the kernos or offering table in the temple at Malia was used to offer grains and honey to her. In general, the regenerative aspects of bees were a key symbolic attribute of a Minoan goddess.

Honeycomb imagery was also prevalent in various tombs, symbolizing the renewal to be found in the afterlife—renewal in the sense of change in form, not necessarily size (i.e. bees start as an egg, then larva, followed by pupa before fully grown).

Bees’ tendency to swarm and even dance in synchrony (and the fact that they congregate in hives) serves as a symbol of community and oneness.

And while more prominent in Ancient Greece, bees were generally regarded as divine messengers that imparted wisdom and eloquence to mortals when imbibed.

Honey in Economy, Trade, & Food

In addition to Minoan spirituality, honey was crucial to the Minoan economy and trade. Not only was it their primary source of sweetener, but it also provided them with a versatile food source with substantial nutritional value. Honey was a highly coveted additive of alcoholic beverages like mulled wine as well.

Honey in Skincare & Medicine

Honey was used as a skincare product and ointment across multiple ancient civilizations throughout West Asia and the Mediterranean, especially during The Bronze Age. Honey, often mixed with olive oil, was and is still used to hydrate, soothe, and exfoliate skin, leading to a more youthful complexion. Due to its anti-inflammatory and antiseptic properties, honey was applied to wounds for enhanced healing and to prevent infections.

Needless to say, honey was an elixir of life and longevity to countless civilizations, including the Minoan civilization.

Sources

- A Re-Examination of the Malia Insect Pendant. American Journal of Archaeology: LaFleur, et al.

- Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete by Rodney Castleden

- Natural History of a Bronze Age Jewel Found in Crete: The Malia Pendant. The Antiquaries Journal: Georgios Mavrofridis, et al.

- Truth Lies in the Details: Identifying an Apiary in the Miniature Wall Painting from Akrotiri, Thera by Irini Papageorgiou